Book Review of Amy Wallace's The Prodigy: A Biography of William James Sidis, America's Greatest Child Prodigy

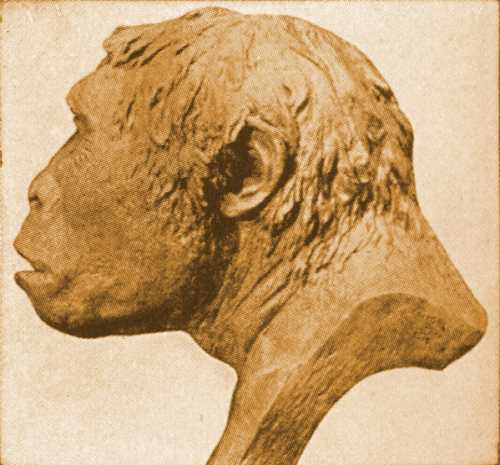

(PD) Java Man

Copyright ©2008-2021 — updated February 12, 2021

From the eyes of java man,

is the belief that you think as he.

From the eyes of a non-prodigy,

is the belief that prodigies think as she.

Portions of the following review are taken from Myths, Facts, and Lies About Prodigies: A Historiography of William James Sidis and from my unpublished notes under the working title of Myths, Facts, and Lies About Prodigies.

Also see Was William James Sidis the Smartest Man on Earth? The World's Smartest Man?, Intelligence Versus IQ, The Mind of Prodigies, and Myths, Facts, Lies, and Humor About William James Sidis - Part 1.

The reader should be aware from the first that it is impossible for anyone to know the heart and mind of William Sidis or anyone else except for one's own self. It is more than a little absurd that a frenzy of myths have been created about a man who was little known while alive, and even less known today. Relative to William Sidis' life, for myself the final answer to all questions will forever remain "I don't know." Never in my life have I researched a topic so satiated with exaggerations, fantasies, and outright lies as what is found in the William Sidis story. The following book review makes no claim whatsoever of it possessing true knowledge about William James Sidis the person.

Is it not a curious thing that the human mind so prefers to believe in the words of a book, whether the words be true or false? Each sect has for its truth a book, the books being accepted with full faith that the words must be true, for after all, as it is believed by each sect member, if the words claim of themselves to be true, then surely the words must be true. Whether the sect be Abrahamic or atheist, whether creationist or evolutionist, the sect members have for themselves books that are believed to hold the ultimate truths, and the believers in the precocity of William Sidis have for themselves the 1986 book The Prodigy: A Biography of William James Sidis, America's Greatest Child Prodigy.

Amy Wallace is the author and coauthor of several books including The Secret Sex Lives of Famous People, The Two: The Story of the Original Siamese Twins, Desire, Sorcerer's Apprentice: My Life with Carlos Casteneda, The Psychic Healing Book, and several volumes of The Book of Lists. It is common for authors to publish in different genres or to write experimental pieces, and so Wallace's writing background is not lessened by her choices of genres. Nevertheless, the background does show the trend of popular trivia, while an absence of experience exists within the genres of history, psychology, physics, religion, and philosophy, which were important influences in the life of William Sidis. An author cannot write useful information about a topic that the author does not possess knowledge of, and the information within The Prodigy was written without a knowledge of the topics that colored the life of William Sidis. It is recognized, however, that a writer must write what the public will buy, for if the public will not buy the author's book, then the author cannot become a popular writer. The popularity of Amy Wallace's books, and all other authors', are not judged by the books' quality, but rather the popularity is measured by what books the buying public chooses to purchase, and it is the buying public that determined the popularity and acceptance of The Prodigy. Regardless of whether the information within The Prodigy might be true or false, the final judgment of the book's acceptability was determined by the buying public, and the personal role of Amy Wallace, as the author, is now immaterial and separate for the purposes of this book review.

Within The Prodigy are references to Sarah Sidis' The Sidis Story, Norbert Wiener's Ex-Prodigy, Kathleen Montour's The Broken Twig, Dan Mahony's records, and several other sources including newspaper articles. The Prodigy provided a sizable quantity of quotes, which were useful for verifying where the quotes allegedly originated. In spite of being a good source for references, The Prodigy was not well organized by topic nor by chronological order. The book's design was built upon the copying, paraphrasing, and restructuring of words and phrases from other authors' articles without attention to how numerous stories conflicted with other stories throughout the book.

It is unfortunate that the errors within The Prodigy have become the primary source for the majority of current beliefs about William Sidis. Hundreds, if not thousands of authors, chose to not research beyond the reading of The Prodigy, and while holding up The Prodigy as if an inerrant holy book without flaw, the authors accepted the words within The Prodigy unchallenged.

To illustrate but a few of the inaccuracies within The Prodigy, the book's comments on The Animate and the Inanimate displayed a lack of knowledge about physics and prodigious talents: "Indeed, the book explores the theory of black holes... and it must be remembered that it sprung from the mind of a boy in his early twenties...".(page 160) Regardless of popular opinion, The Animate and the Inanimate did not speak of black holes, nor of dark matter as some individuals have claimed in recent years. The Animate and the Inanimate was a speculative theory, a simplistic mental game of applying logic to how the laws of thermodynamics might behave if reversed. As Sidis himself stated in the preface of The Animate and the Inanimate: "This work sets forth a theory which is speculative in nature... The latter part of the work, which deals with the theory of the reversibility of time and the psychological aspect of the second law of thermodynamics itself, is a purely speculative section." The Animate and the Inanimate did not present new thought, nor did it pretend to. It is unknown if The Prodigy's comments on The Animate and the Inanimate were structured upon a lack of comprehension of what William Sidis wrote, or if The Prodigy purposefully sensationalized The Animate and the Inanimate to make Sidis' book appear greater than it actually was. Regardless of the cause or reason, The Prodigy presented incorrect information about William Sidis and The Animate and the Inanimate.

The Prodigy also did not recognize that William Sidis' theory was a full decade past the cutoff age of exhibiting prodigious intelligence. Most any healthy ten year old child with above average intelligence and an education in thermodynamics would be able to conceive of the theory within The Animate and the Inanimate, and a prodigious intellect would have easily understood the theory's concepts by no later than five years old. Regardless of whether Sidis wrote The Animate and the Inanimate when fifteen or twenty, the theories within the book were not remarkable nor of a prodigious level. I am not saying that The Animate and the Inanimate was Sidis' best work, nor am I saying that the book was the pinnacle and exhibition of Sidis' potential intelligence, but rather what I am saying is that the book's topic itself was mediocre at best. The material within The Animate and the Inanimate is not indicative of a prodigious intellect, and only the non-prodigious mind might interpret it otherwise.

The Prodigy also presented the common and incorrect non-prodigious belief that new theories must arrive from professional scientists and be logically sequenced from previously established theories. There is no shame in not being a prodigy, but there does exist shame for the non-prodigious individual who lays claim of understanding the prodigious mind, as there is also shame for a prodigy to claim an understanding of the common mind. It is not possible for the non-prodigious mind to comprehend nor to interpret the prodigious mind, and the non-prodigious The Prodigy was guilty of pretending to have presented an accurate interpretation of William Sidis. From the very beginning it was not possible for The Prodigy to have been an acceptable history or biography of any prodigy.

On page 181, The Prodigy rudely referred to William Sidis' historically significant book Notes on The Collection of Transfers as "arguably the most boring book ever written." Biographers and the public have in almost all known instances ridiculed Sidis for his hobby of collecting street car transfers. The insensitivity of the public and biographers is inexcusable. The explanation for the tickets' importance does not belong here, but suffice it to say that the tickets might have been William's most precious moments, not only of his childhood but also of his personal system of structured logic. From my personal notes, "the ridiculing of William Sidis for his hobby was perhaps the single most cruel thing a person could have possibly done to him." There was no excuse for biographers to have perpetuated such negativity against Sidis. William Sidis was a human being with feelings, and all biographies, past and present, ought to have recognized that fact.

It was ironic that in my notes, written while reading The Prodigy: "By page 83 I am wasting time, I will skip forward and brief the remainder of the book." I instead decided to endure the reading of the whole book, but only through the determination to gather knowledge of the book in spite of The Prodigy being excruciatingly boring to me. I had to smile when I came across The Prodigy's opinion of Notes on The Collection of Transfers, for indeed the differences of interests and opinions do illustrate the differences between prodigious and non-prodigious interests. The Prodigy was incapable of recognizing Sidis' interests in street car transfers, and for The Prodigy to not have recognized such a simple thing, it was to be expected that The Prodigy would fare no better with complex topics.

While it is always expected for an author to color a biography with personal interpretations of the individual being written about, it is not expected for a biography to unduly sensationalize events, and it is thoroughly unacceptable for a biography to purposefully rewrite sequences of history. A brief and simplistic example of the contradictions, sensationalism, and twisting of history throughout The Prodigy is found in how the book altered information from Sarah Sidis' The Sidis Story. Below are quotes from within The Sidis Story along with a numbering to help mark sequences.

"...Boris was astonishing Harvard.

We were married at Christmas that year, the year we both entered college. ...Students and professors used to come, for conversation and for experiment. It was on those afternoons that Boris conducted much of the psychological research that enabled him to formulate the principles he outlined in his first book, "The Psychology of Suggestion."

...James came. James gave to Boris's life its definitive slant. First James taught him psychology, and then they taught each other by studying together. ...

James said to me, "If they call me genius, what (1)superlative have they saved for this husband of yours?"

...After his entrance examinations showed his professors what he was and what he knew, they let him take the most advanced courses, and gave him a scholarship. At the end of one year he was given his BA. degree.

It took no persuasion on my part to get him to go back a second year, for he had found the teachers so simple and so intellectual. He got his master's degree in that second year, with the help of a Korgan fellowship that paid him enough for us to live on.

In the third year of my student days, he was not enrolled at Harvard, but taught a course in (2)Aristotelian logic for Royce.

(3)My domestic diplomacy was called into play to get him back for his Ph.D. degree.

(4)"Red tape! Red tape! Letters! What do they mean!" It took some doing on the part of Royce and James to convince him that three letters tacked onto his name might some day help him do work that he very much wanted to do. (5)They coached me in how to persuade him.

But his college teachers did not want him to be a college teacher. "I am in a (6)rut," said James. "I teach the same thing over and over again year after year. I have too little time to (7)really study, or (8)really contribute anything to the world. It is a question to me whether my teaching means anything at all to 90 per cent of my students. You mustn't teach, for you can do greater things."

In February of my senior year in medical school James sent Boris down to New York City, with a (9)letter to Teddy Roosevelt, who was James' friend and admirer.

Roosevelt had been elected vice president, and had only a few more weeks to act as governor of New York. He talked to Boris for two hours.

"Look here," Roosevelt said. "I have never met a man like you. I can't let you go back to Boston, because I have only a few more weeks to do things in New York. and we must have you here."

Associate psychologist and psychopathologist of the New York state hospitals for the insane was the position Roosevelt gave Boris to keep him in New York.

For the first time in our four years of marriage we were separated for a few months, for I stayed in Boston to graduate from medical school that June.

The faculty wanted Boris to submit a (10)thesis for his Ph.D. degree. "Thesis, bah!" said that one. "They know what I can do, and whether I should have their degree."

Then the faculty wanted him to come back to Harvard for an (11)oral examination.

"That I'll not do!" said this wild Russian.

(12)I went to Royce and said, "What shall I do with him. He won't submit a thesis, he won't come back for an oral examination!"

(13)"I will meet with the faculty and discuss it," said Royce.

(14)Harvard mailed Boris his Ph.D. degree in June. James said they didn't do as much for him."

On pages 16 and 17 of The Prodigy it is stated:

"The years 1896 and 1897 were important years for the Sidises. Boris taught (2)Aristotelian logic for Royce at Harvard...

Boris came up the stairs into the apartment, He seemed all excited. 'James called me into his office today...'

"He wants me to see Teddy Roosevelt. I walked into James' office. He made me sit down, He said he and Palmer and Royce had had a long talk about me. First, James asked me what my plans were after I got my degree. I told him that I had applied for several teaching positions in the West and the South. He said, "You don't want to teach. You'll get in a rut. Look at me - (6)I'm in a rut. I have too little time to (7)study, I'm not (8)contributing anything to the world. We can't have this happen to you. I'm going to give you a (9)letter to Teddy Roosevelt. He'll only be in New York for a short time before he goes to the White House."'"

...Then, while Boris was in New York, Harvard requested that he submit a (10)thesis for his Ph.D. His professors suggested The Psychology of Suggestion, the brainchild over which he had been slaving. He refused vehemently - no school, not even Harvard, was going to get credit for his work. When they realized he was refusing to submit this or any other thesis, the university officials relented, asking him to come to Boston for an (11)oral examination. Boris again declined. (4)"Red tape! Red tape!" he ranted. "Letters! What do they mean!"

{3 - first episode is missing relative to 4 of getting Boris back for his Ph.D., and 5 of Sarah being coached by Royce and James.}

Again (12)Sarah appealed to Professor Royce. (13)"I'll meet with the faculty and discuss it," Royce replied.

(14)Harvard mailed his Ph.D. in June, waiving all ordinary formalities. James told Sarah, "They wouldn't do this much for me. ...If they call me a genius, what (1)superlative have they saved for this husband of yours?""

The Prodigy quoted from The Sidis Story, but twisted the words, twisted time frames, the book inverted sequences, and invented things unsaid. The Prodigy does not possess the qualities to be deemed a book of history, a book of psychology, nor a book of philosophy, but rather it is merely a book of sensationalized trivia and hearsay, a hardback tabloid, the very thing that the buying public will always prefer over an academically researched book.

Is it not a curious thing that a book might be written about a topic, and yet the author not expect the book to be read by individuals who share a similar talent as the book's topic? It is absurd for a book to be written about prodigies, and the author to not expect prodigies to read the book, and yet The Prodigy was apparently presented to the public with the belief that no reader could possess a memory sufficient enough to recognize the twisting of time frames. The Prodigy claimed to present valid information about prodigies, but only a non-prodigious mind could believe the claims to be true.

The Prodigy also invented a negativity about William James by omitting the word "really" (6), rendering Sarah's "I have too little time to really study, or really contribute anything" to have said "I have too little time to study, I'm not contributing anything." The average reader may not deem the omissions significant, but the reader will at minimum subconsciously register the difference and mentally create a negative pattern about William James' contributions to the world. Regardless of an individual's opinion of William James, it is always wrong to misquote a person's words.

As further illustrated in William Sidis - Smartest Man on Earth?, many of the claims within The Prodigy fully disagree with firsthand accounts. The whole of The Prodigy swims within similar contradictions, twisted time frames, and inventions as shown above. The Prodigy is useful for its references, and perhaps as a novel, but the book should never be relied upon for fact nor for historical accuracy.

It is interesting to me that of the known book reviews about The Prodigy, none mentioned the obvious breaks in logics sequencings, nor were there any mentions of obvious twistings of mental patterns throughout the book. It appears that the general public simply placed full faith in the book's unsubstantiated claims that William Sidis was the world's greatest prodigy, and the myths continue unchallenged today by the general public.